In brief: We returned to Rome for one art exhibition, Caravaggio at the Palazzo Barberini, but – inevitably in this city – discovered much more.

Rome is rich with artistic treasures at any time. Special exhibitions – like the ones we caught, the Caravaggio at the Palazzo Barberini or the Munch at the Palazzo Bonaparte; or the ones we didn’t, like a Picasso collection – makes an art lover want to linger for a long while.

(For other sights we visited around the city, click here to see the post: Rome Visit – Vedute di Roma)

Caravaggio at the Palazzo Barberini

In our travels, we’ve been fortunate to see so many of the paintings of Caravaggio. But we went to the Palazzo Barberini – and indeed decided on a fresh visit to Rome – mainly for the opportunity to see 24 of them together.

It was an exhibit that truly illuminated his genius – and wowed us. We saw again his mastery of light and dark for dramatic purposes. But the exhibit showed how he saw light as a tangible expression of the spiritual in this dark world and of the artist’s power to reveal it. Familiar with hardship and trouble, he also portrayed the human cost of being touched by the spiritual (as with saints, hermits, the artist, or Jesus himself) and how the divine elevated even the lowest ranks of people.

Here are a few of our favorites (including three from the Francesi chapel nearby). It’s worth taking some time with them to let those qualities shine forth.

The Conversion of Saul – in this chaotic scene, the light from the upper right blinds Saul and his captor, stuck amid the weeds and horseflesh, while even Jesus must be restrained.

Arrest of Jesus – this extraordinarily complex work of human frailty was the highlight of the exhibit. Judas, a somber Jesus, and a clad soldier are locked in an embrace while an apostle flees toward light from Judas’ all too human betrayal – and from the barely visible lamplight held by Caravaggio himself.

The Calling of St Matthew – One of three paintings commissioned for a chapel in Rome’s San Luigi Francesi church, this was a favorite of Pope Francis for showing the burden of being summoned from a mundane life to serve the divine. It presents the most remarkable interplay of light from a darkened Jesus on the right against Matthew’s dimly lit impulse on the left to stay obscure. Its complexity is very well discussed in a recent NYTimes piece.

David with the Head of Goliath – even the dead giant gasps in wonder at his defeat, while the troubled and pensive boy thrusts the reality of that death toward us from the dark

Supper at Emmaus – the already dead Jesus quietly startles two of his followers at a meal long after the Last Supper, while one grabs the table for support and light glows on the very attentive innkeepers

The Cardsharps – this work, which we know from the Kimbell Art Museum, revels in subtle details such as the wily advisor with worn gloves, the hidden cards, plus the glow of both the innocent and the guilty.

Sick Bacchus – an early work with the artist as a kind of madcap model in a greenish hue

Flagellation of Christ – brutality torments the divine in this very humanized portrait of a beaten Jesus, whose own light seems to offer grace to his tormenters

The Three Paintings about St Matthew from the chapel at San Luigi Francesi church – The Calling, the Inspiration (in writing the Gospel), and the Martyrdom, in which human brutality again contrasts dramatically with the call from heaven.

Martha and Mary Magdalene – in a more subdued but resonant work, the vain and earthy Magdalene is struck by the spiritual light that will convert her and is also reflected in her mirror.

Narcissus – another early work not fully agreed to be Caravaggio’s, but the dark pool of thought is remarkably well done

Edvard Munch at Palazzo Bonaparte

Art and Rome – a match. The Italian Renaissance and Baroque masters? Of course; the Caravaggio exhibit motivated us to come here. Expressionists and futurists of the 20th century? Yes.

But we happened to pass the Palazzo Bonaparte one day and saw there was a Munch exhibition there. Anguished Norwegian visits sunny Italy…why not?

The renovated palace wasn’t of much interest. But the exhibit contained an extraordinary collection of familiar and unfamiliar work, while presenting a superb investigation of Munch’s artistic power throughout his long life.

Woman:Sphinx, 1894 A symbolist rendering of the stages of life, with the young one to the left facing the future and the broad sweep of the seashore, the mature sexual woman in the middle, and the sad aging woman on the right, nearly encased in her dress and the space. The ambiguous male isolated and framed on the right, with a downcast or thoughtful posture but squiggles and slashes of color, seems to stand apart from the female life cycle.

Vampire, 1895. At this time, as Freud brought sexuality and desire into the foreground, the bohemian lifestyle of many artists also pulled sexuality and love out of the prurient dark. In a meme that Munch re-used again and again – in a range of media – this strange embrace stands out. It was a friend who used the term Vampire. But for Munch (who originally titled this “Love and Pain”) it expressed the power of women for danger and comfort, the needs and fragility of men, and also a mutual yin/yang embrace.

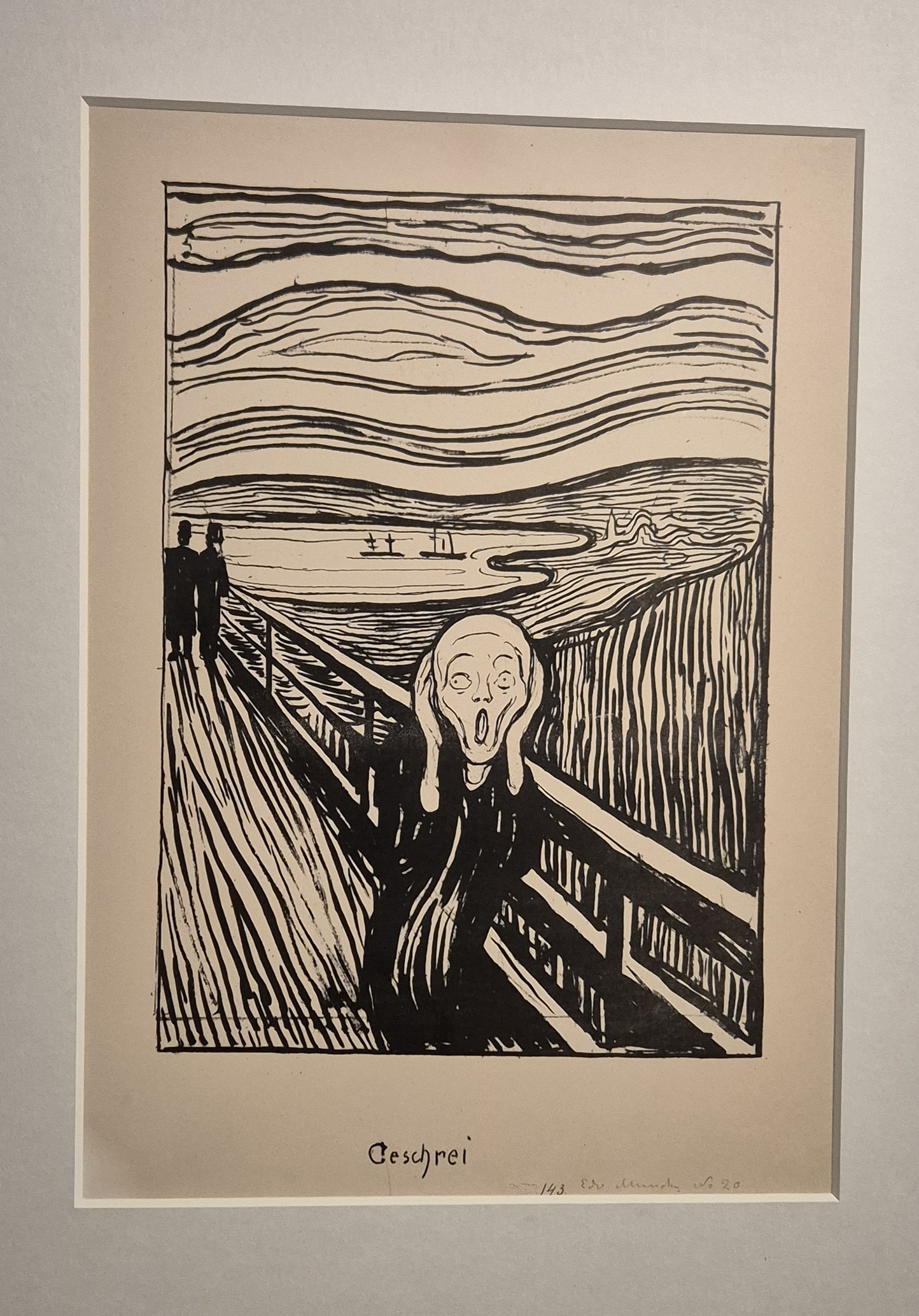

The Scream, 1895. This is a lithograph of his famous painting, with the disturbance that transforms the landscape perhaps even more striking. The only stability is the railing extending endlessly, but that also hems in the figure. Meanwhile, the figure’s distress is ignored and isolated from the receding figures in the back.

Kissing Couples in the Park, 1904. Munch often used the image of a kiss, where the figures are distinct but the faces seem to merge with each other, again with a yin-yang concept. It was an image of love, the merging of two people, and of the threat of losing oneself. Here the blobby colorful elements of the landscape enhance the energy and vitality to be found in these amorous couples.

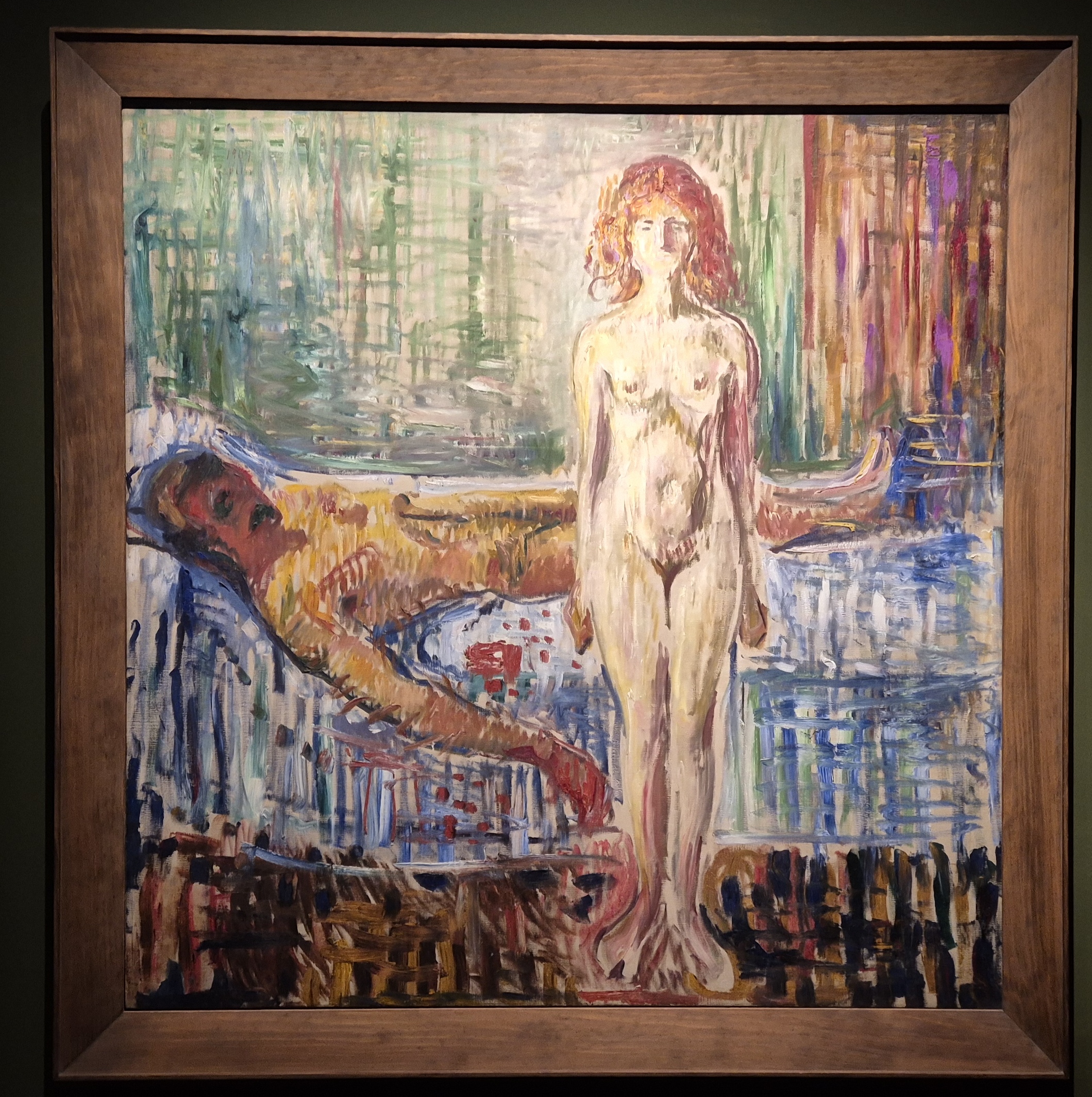

The Death of Marat, 1907 Munch had a long turbulent affair with Tulla Larsen that ended with her attempted suicide and with a gunshot wound to his hand. Munch’s troubled mind about women, due to the attraction and psychic threat he felt with them, is evident here. In the painting, he echoes David’s famous painting of the killing of the revolutionary Marat by a woman. The emotional temperature is extreme with the two figures oriented in opposite directions, blood dripping on the sheets, and streaks of clashing paint across the canvas.

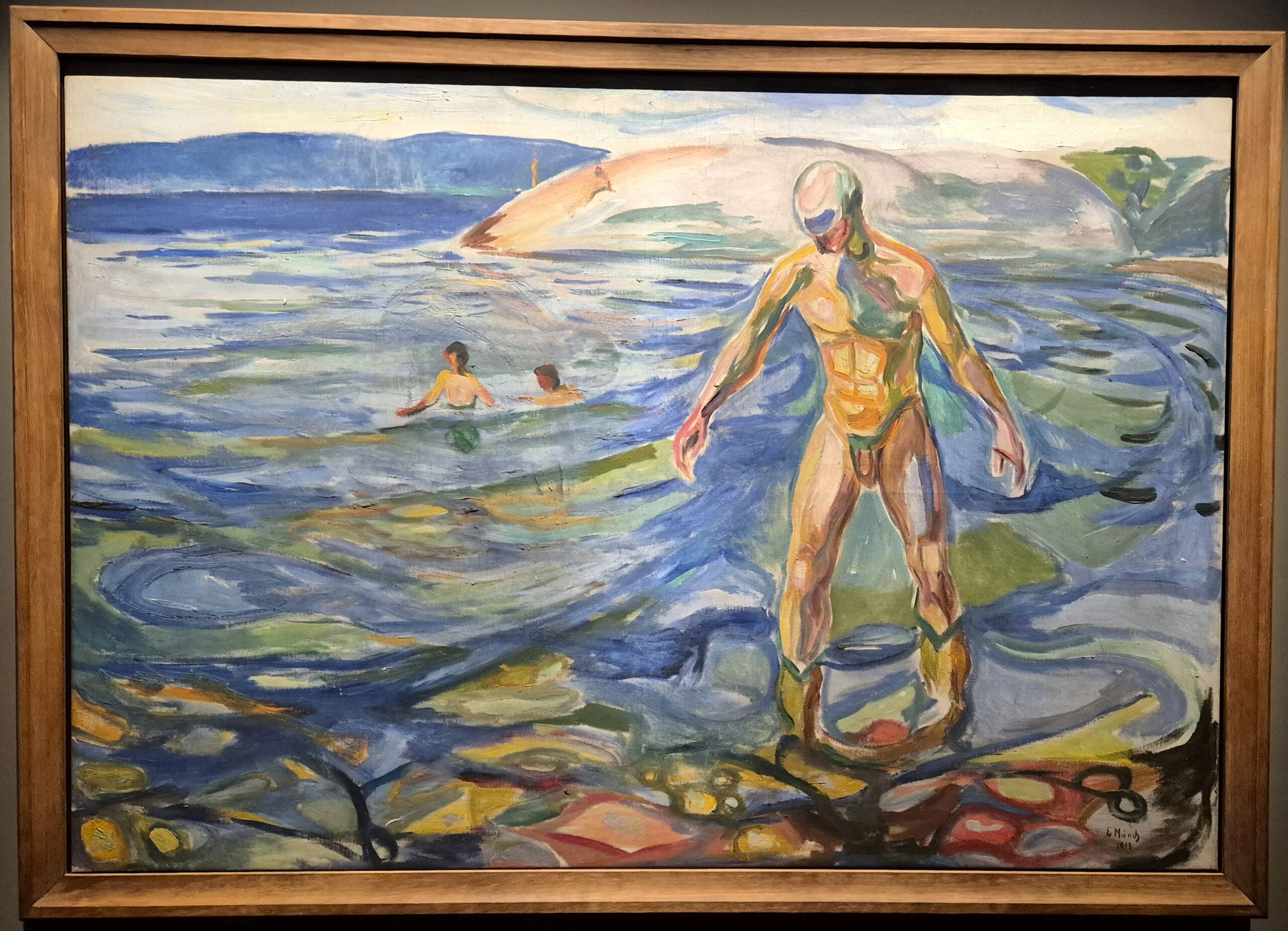

Bathing Man, 1918. In the early 1900s, Munch put himself in a sanatorium, sobered up, and found a new mental stability. He embraced the naturist movement of healthful seaside activity and living. In this painting, the main figure gingerly steps over rocks in order to merge into a landscape much more placid than Munch’s prior work, with brilliant sun-dappled colors. Many have seen a sense of rebirth from the end of World War 1 in this motif as well.

Digging Men with Horse and Cart, 1920 Munch saw the beauty in nature and how the manual labor of his countrymen fit harmoniously into it. Like van Gogh, the brushstrokes express the vitality of things out in the brilliant sun.

The Artist and His Model, 1921 With a room canting toward the viewer, rendered in brilliant colors, lushly and impressionististically, Munch renders an ambiguous but provocative scene. The bed suggests an intimacy that the two figures, clad so differently, contradict. Instead they look heatedly out at us, the viewer, with darkly shadowed faces. The woman seems much like earlier Munch portraits of threatening Salome figures.

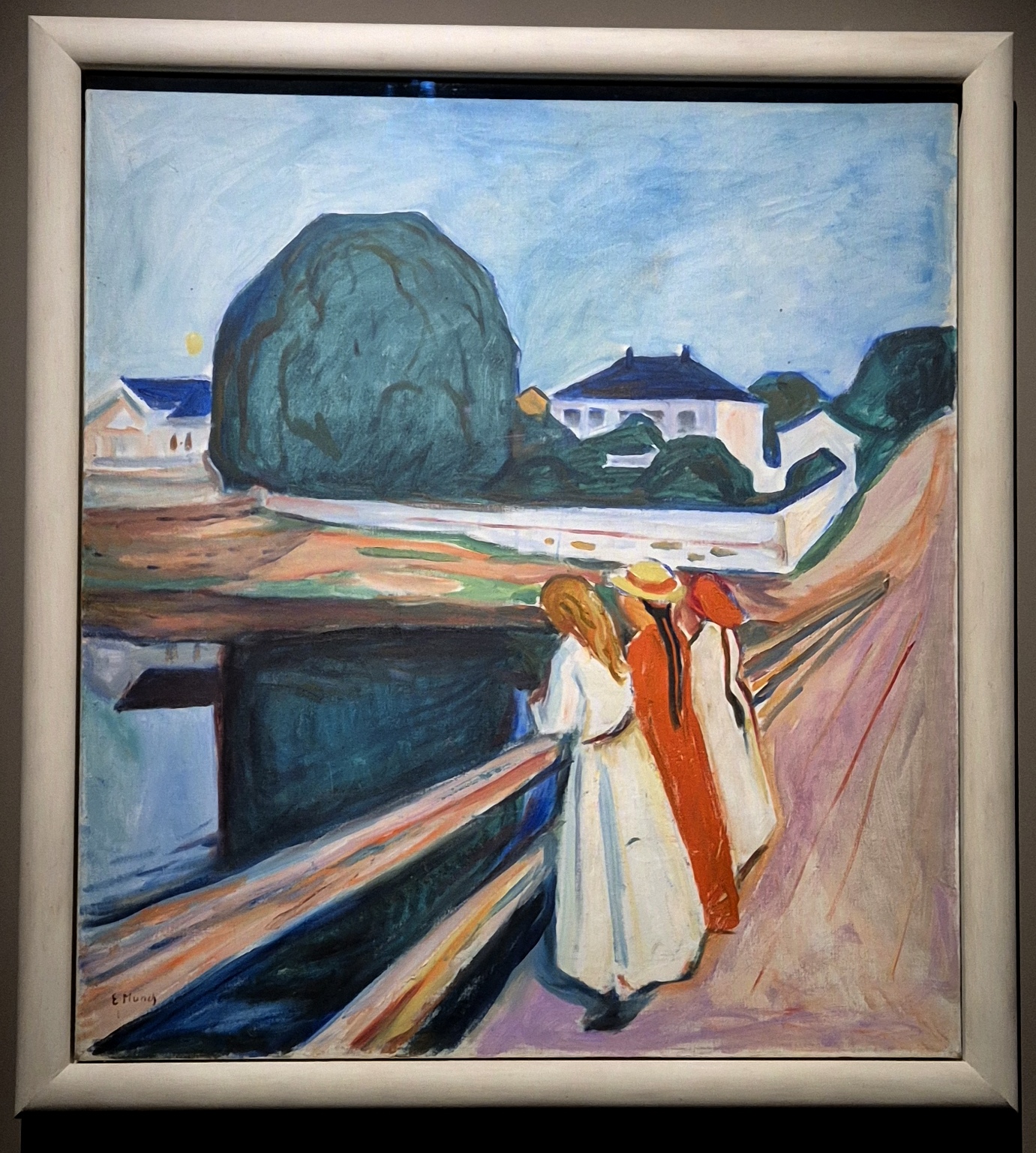

Girls on a Bridge, 1927 Munch did many wintry landscapes later in life, capturing a subtle energy in nighttime scenes with mysterious, shadowy figures. This evening scene – a later version of a setting he continued to paint many times from 1901 on – seems much different. It’s an image both tranquil and hopeful, but full of resonant meanings. The girls are set on a bridge similar to the famous Scream, both on their way, but also caught between beginning and end. They stare into the distinct, but oddly transformed shadows of the town in the water, as if reflecting on life itself.

Self Portrait between the Bed and the Clock, 1943 Throughout his life, Munch did many self-portraits. Toward the end, he depicts himself as a nearly skeletal figure in prim suit, almost as stiff as the clock with no hands, facing his own shadow along the floor. With Time looming to one side, the nude woman and bed on the other side affirm the life-force of the body, birth or re-birth, and his own past – as do the paintings by the artist on the back wall.

Hidden Treasures – Villa Farnesina

When we return to cities we have visited before, we like to find less touristed, quieter pleasures. So, in Rome, we visited the 500-year old Villa Farnesina in the Trastevere section of the city.

There we discovered a celebration of love – in public halls frescoed by Renaissance masters like Raphael and del Piombo, on window panels where nubile mythic figures still cavort, and in lusciously painted private rooms. With few others around us to share them.

The Loggia of Cupid and Psyche, currently the entryway of the Villa – by Raphael and his workshop. This lushly decorated hall alludes to the full complex and lurid story of the beautiful woman Psyche, who captivates the god Cupid, son of Venus. Cupid bargains with Zeus to help Zeus with his love affairs in exchange for elevating Psyche to immortal life so Cupid could wed her. The two ceiling panels show Cupid’s plea to Zeus in the far panel and then the wedding party in the near one. Other scenes from the story and mythic figures fill the corners and arches, making the loggia quite lively visually.

A closeup of the wedding scene on the ceiling of the Raphael loggia. Cupid and Psyche are seated on the right side of the table, with the winged Bacchus pouring much wine and the three Graces blessing the event. Zeus seems to be connecting with a woman across the table.

In another large colorful room of the Villa, Raphael’s fresco The Triumph of Galatea doesn’t depict the main story. That’s a sorrowful tale of a romantic triangle where Galatea cheats on the one-eyed giant Polyphemus with a lovely shepherd boy who is soon crushed by a boulder that Polyphemus hurls. Raphael instead chose to glorify his “idealized beauty” as a Venus whisked up to heaven from a seashell amid a kind of orgy of lovemaking, winds, waves, and even blowing horns (on the left).

The richly colored ceiling and walls of the Galatea room by del Piombo depict a myriad of stories from Ovid and astrological references to the birth date of the villa’s owner Chigi. To the right, Luna guides the moon across the skies. To the left, a startling angel heralds the slaying of Medusa by Perseus, while a few heads seem to discuss where to go for lunch.

Window treatments like these throughout the villa, in a style reminiscent of Pompeiian art, feature countless enchanting figures in a perpetual dance.

In the Chigi bedroom upstairs, scenes of love and lovemaking abound under a golden coffered ceiling. The main wrap-around painting by Bazzi (known for some reason as Il Sodoma) is another marriage scene in which Alexander the Great offers a crown to seal the deal with his great love Roxana. Notice to the right of Alexander the painted colonnade leading onto a virtual landscape.

Also in the private area for the Chigi family, this salon room by Peruzzi celebrates the Roman deities that Chigi liked with trompe-l’oeil frescoes. Enlivening the space are virtual statuary, imagined views past large columns over the countryside (with correct perspective visually), and rich detail.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Italy, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)