In brief: Three dramatic historical themes filled the Palace rooms: how the republic emerged, the massive 1755 earthquake and renovation, the role of water in Lisbon.

One branch of the Museum of Lisbon is housed in the grand villa of the Palacio Pimenta in Campo Grande. Our Sunday visit to Pimenta, one of many over time that brought us insights into the city, gave us an engaging local history lesson with style.

And what better place for fascination than a villa with such a spicy history, reportedly built by King John V as a cozy spot for his mistress to await his – and recently our – visits.

We began, as King John did, mounting this tiled staircase leading to the upper chambers, a climb he would eagerly take in visits to his mistress.

Three other themes, however, caught our attention that day.

The first theme was the fitful emergence over a century of the Portuguese republic that displaced the long-time monarchy. Second, the renovation of the city due to the massive destruction of the 1755 earthquake. Third, the role of water in the growth of the city, from the ports of the River Tejo to the aqueducts dating back to the Romans.

1755 earthquake and rebuilding

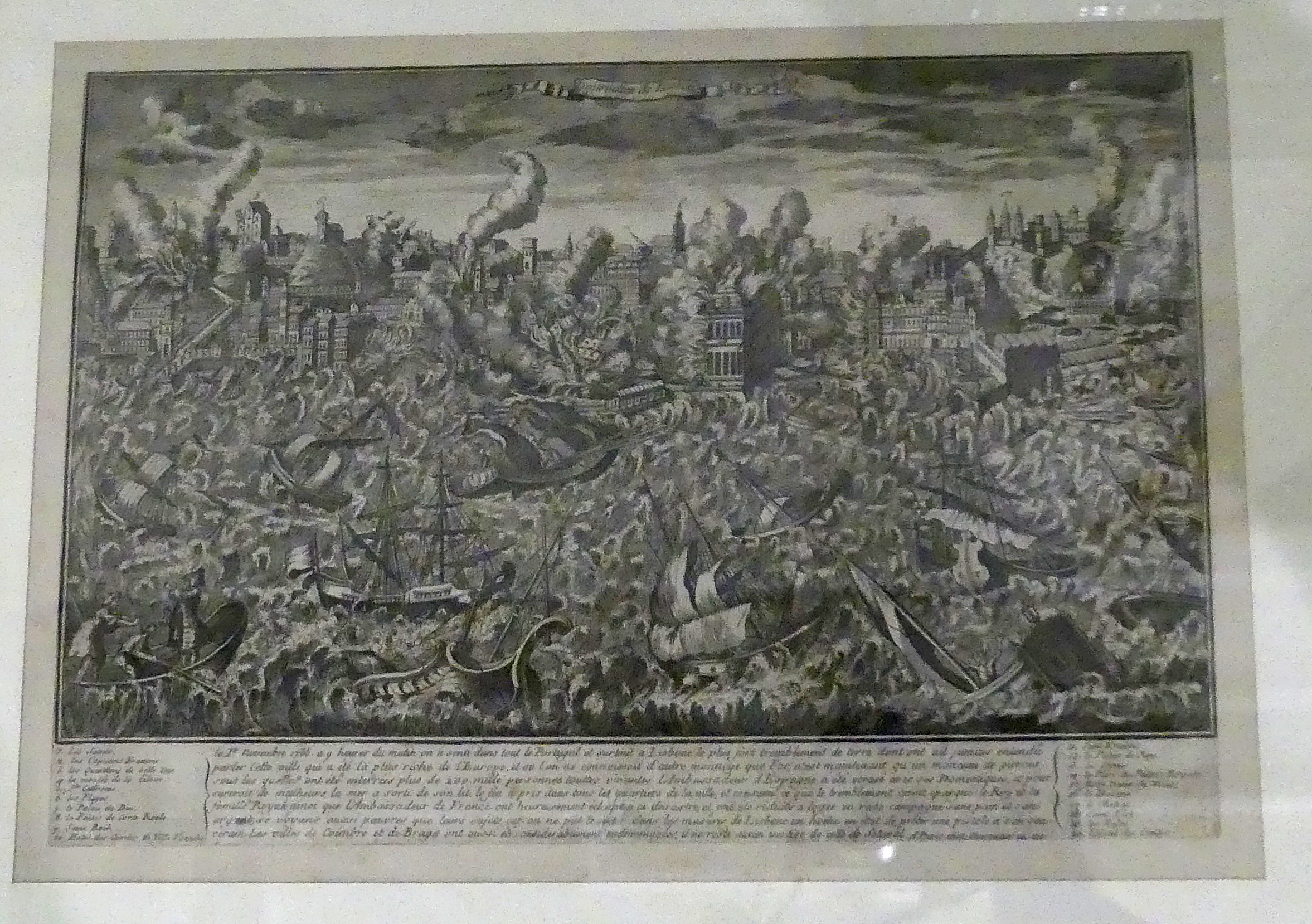

The museum shows numerous prints published at the time of the earthquake – literally, breaking news – trying to show its devastating force and fiery aftermath. This tumultuous, frightening image of 1 November 1755, All Saints Day, also makes clear the turbulent effect on the River Tejo and the vessels that had been nestled at the city’s riverfront.

Several engravings compared the city before the quake and as it happened.

Depictions of the aftermath were also well documented. Here are four images of buildings ruined by the earthquake. Artists’ interest in these ruins recalled the artistic attention paid around this time to the ancient ruins of the Roman era across Europe.

A whole room is devoted to honoring the monarch and the minister responsible for rebuilding Lisbon rapidly after the earthquake. Most of the portraits glorify the formidable manager of the reconstruction, the minister soon named the Marques de Pombal. To the right of this picture, there were several models of the statue honoring his king Joseph I at Praça do Comercio in the central city. Pombal is also noted on the statue.

Part of the room covers the intriguing story of an alleged assassination attempt on the king. The prosecution of the wealthy family held responsible was led by Pombal himself as chief minister.

The emergence of the Republic

On exhibition at the time of our visit was a look at the late 19th century renovation of the Rossio plaza downtown including the building of a commemorative statue for King Pedro IV.

Known as the Liberator, Don Pedro was the first regent of Brazil and back home, among other things, established a constitutional monarchy for Portugal in 1823. It took nearly 90 years before the country became a republic without a king in October 1910. Several paintings and displays introduced the royalty during that period and followed the mounting popular displeasure with the monarchy.

These two early 19th century souvenir panoramas of central Lisbon would be mounted on folding fans. The top image is Praça do Comercio, looking much like today, with the statue of King Joseph I, the rebuilder of Lisbon. The lower picture is the Rossio plaza, with the same grand opera house and theatre as today in the backdrop, but without the wiggly tile or statue of Pedro IV of the renovated plaza.

Water and Lisbon

Several rooms addressed the valuable mercantile trade via the ports along the River Tejo as well as the delivery of water via the “modern” aqueducts dating back to the Romans.

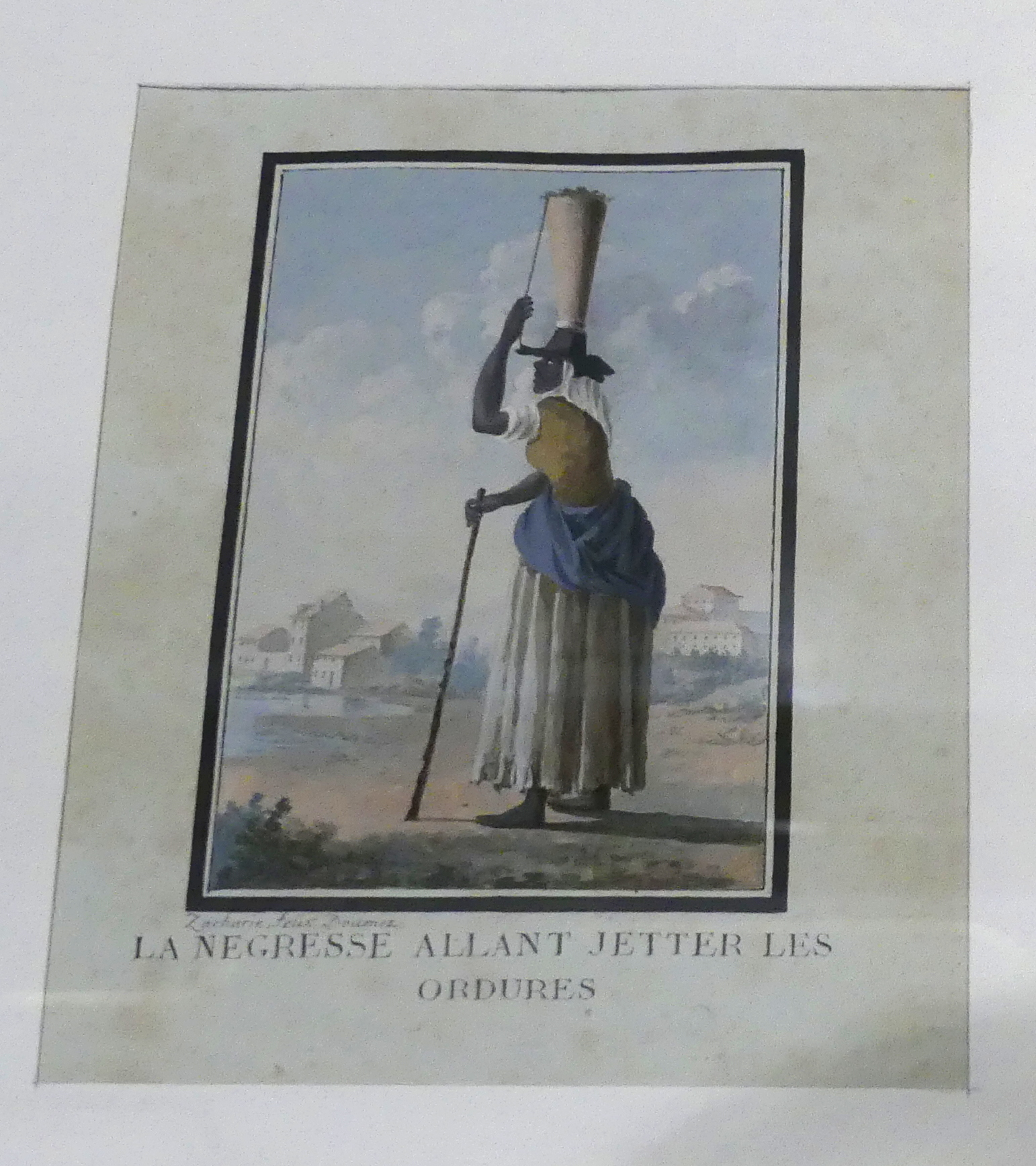

Occasional images of black figures appear in the displays, largely as slaves, including this one of a woman carrying a vessel with human waste for her owners. She would also have drawn water from one of the many public fountains. Perhaps this was a normal domestic task, but the drawing of the act – with the heavy burden and the light stick as support – tells its own sad story.

Gardens

The extensive displays within the grand rooms of the Palacio enjoyably filled in our understanding of this fascinating city. Outside, the Palacio also offered a delightful large garden area, a quiet refuge from the city with a well-known home for at least a dozen peacocks.

A separate part of the villa’s greenspace is a mixture of rose garden and fantasy world filled with the ceramic creations from the artist honored just across the street, Raphael Bordalo Pinheiro. A few weeks earlier, we had visited the boutique museum honoring him (for that post, click here). As we had noted in touring his museum, and as is evident here, he did love frogs. And crustaceans, as are seen in the ceramic figures of a second fountain in the garden.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Portugal, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)