In brief: We finally took the opportunity to go with the flow – visiting the Douro River and environs – after seeing much of the rest of the country.

There are many ways to “do the Douro.” The river starts in Spain and crosses some 200 or more kilometers of Portugal’s prime grape-growing terroir until it weaves through the city of Porto on the Atlantic.

This is often among the first places visited by foreigners to the country, but we kept choosing other options in Portugal instead. Finally, we seized the chance to go.

You can take a wide variety of cruises along the river, stopping at towns and wineries.

You can take the train along the river’s edge, with the especially scenic Eastern portion typically managed by a vintage engine – as we did. Like us, you can drive, partly by the river and partly along the superb vistas atop the Douro’s 300-meter high hills (1000 feet). Or you can just find a tranquil spot, in Porto or along the way, to watch the river flow, while sipping a glass of Douro wine.

You can also enhance the natural experience or history with cultural ones, as we found in plenty at historic Lamego and carved into rocks at pre-historic Vila Nova de Foz Côa.

We even went a bit farther afield, as you can see our related post (click here) about neighboring Viana do Castelo in order to visit old friends; Bragança, to see the home of Portuguese kings; and Arouca, to get a dose of vertigo, swaying on the longest pedestrian bridge in the world.

Douro River

A green patchwork of vineyards as we round a bend toward river town.

Our tranquil spot to enjoy some wine

Our tranquil spot at a vineyard

A typical vista across vineyards above the Douro River

More textured riverside vineyards

Along a narrow section of the Douro by train

A river bend near the Spanish border

A rocky canyon along the Douro, as the train rounds a bend

Historic, Inviting Lamego

Hilly Lamego sits in the heart of the Douro wine district, though not at the Douro River itself. Over the years, it has seen significant historical moments. In the 12th century, the first king of Portugal, Afonso Henriques, who liberated Portugal from Spain and Moorish control, was crowned here, it is said, by the first ever Portuguese parliament of nobles. The church and castle from that time still stand.

Residents, however, speak of Lamego as a crossroads, a place easily accessible now to the larger cities of northern Portugal and Spain, as well as the Douro River, plus attractive to both the Portuguese and agricultural workers from former Portuguese colonies. Seven hundred years ago, Lamego handled extensive trade between Spain and Portugal, especially oriental spices and textiles. By the 18th century, it flourished due to the port and champagne markets. And it has long been a key pilgrimage stop on the way to Santiago de Compostela, with a high altitude church where pilgrims gather.

The main gathering place for residents is this leafy elliptical plaza, with numerous places to eat and drink, along with a few businesses.

Lamego enhanced its standing as a major pilgrimage stop in the 17th century when the bishop established the cult of Nossa Senhora dos Remédios (Our Lady of Remedies) as a healer of illnesses. A splendid baroque church honoring her overlooks the town – high, high atop a staircase of 686 steps and platforms. The stairs were started in 1750, but only finished in 1905. We climbed, but not on our knees, as pilgrims might.

This elaborately carved obelisk makes a distinctive fountain on the climb to the church of Nossa Senhora dos Remédios. Strange figures spew water into the fountain below tributes to the moon, on this face, and the sun on another.

The view from the 17th century church of Nossa Senhora dos Remédios, about 130 meters (or 400 feet) above the main plaza. During this time, Lamego flourished from the wine trade along the Douro River, in part because the region was granted the first ever demarcation in the wine industry to ensure quality. Lamego also carved out a specialty with its Portuguese version of champagne. But soon British companies – the ones still famous for their port wines – colonized that part of the industry.

Apparently grateful to the nobles for making him the first king of Portugal, Afonso built the town’s cathedral, whose original Romanesque tower still stands at the right side of the later Renaissance and Baroque adaptations. The Gothic portal features incredible carved detail, including floral decoration, saints, and other figures engaged in somewhat dubious behavior.

The lovely rose garden in the cloister of the medieval cathedral, the Sé.

This stunning chapel is tucked to the side of the main Cathedral’s cloister, with its effusive baroque carving and tiled decoration.

Narrow medieval streets climb from the elliptical plaza.

Looking out at a lane along the castle walls made of packed stone, with one of the many castle towers in the distance. We are sitting atop the medieval cistern, a barrel vault made of rectangular blocks that gathered rain water to sustain the defenders of the castle. Each block is marked by the worker who carved it, to ensure he was paid for his effort.

The Porta do Sol, Sun Gate, at the castle.

Ancient Art in the Côa Valley

For tens of thousands of years, as far back as 25,000 years ago, inspired artists of the fertile Côa Valley limned the spirits of the plentiful animals around them into the valley’s rock faces. They etched in stone the fervor of huntsmen pursuing those animals for food. Miraculously saved from disappearing under dammed waters by a grassroots protest, and now preserved as UNESCO World Heritage art, those engraved spirits still hunt and graze and feed for visitors like us to see.

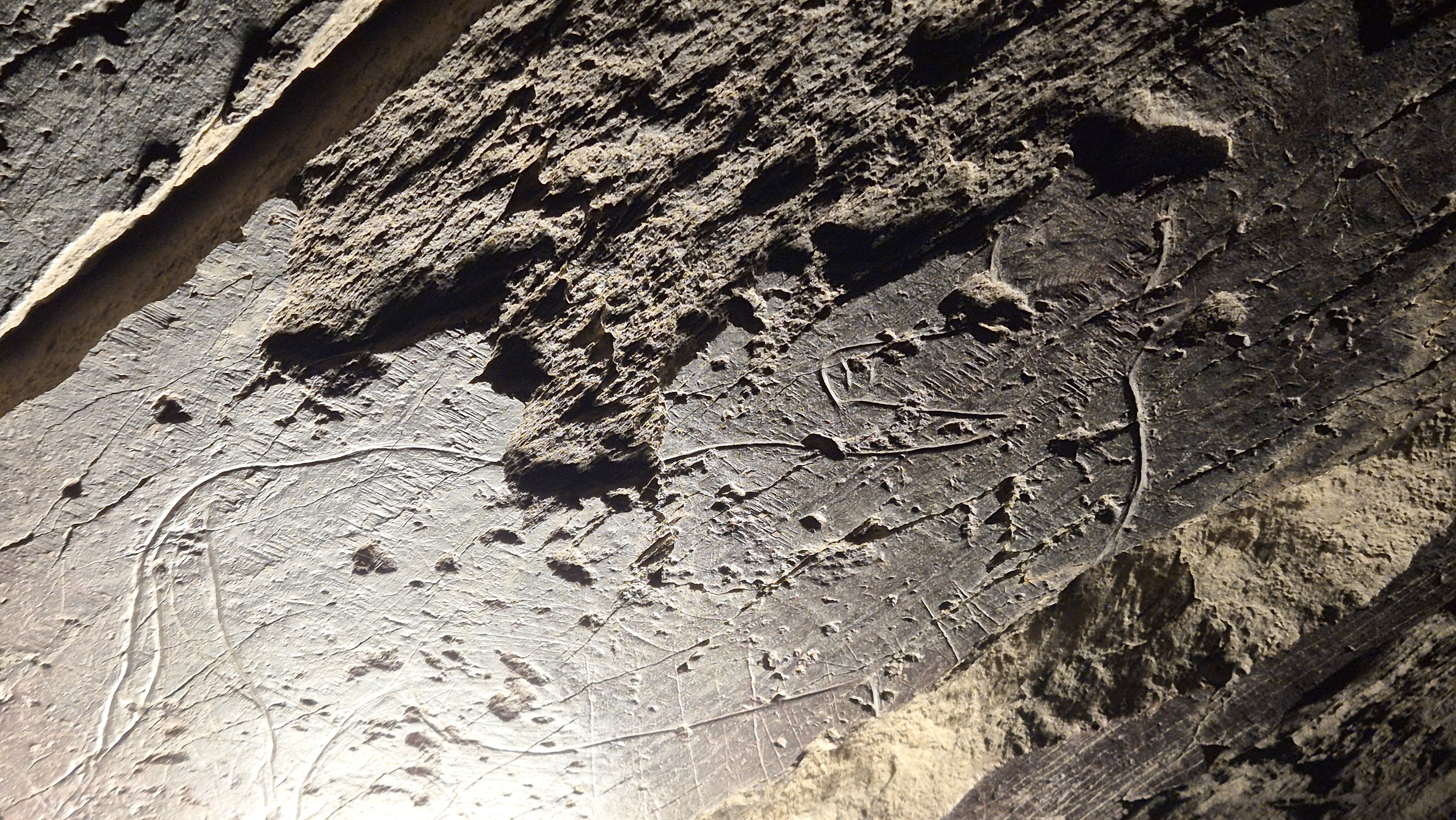

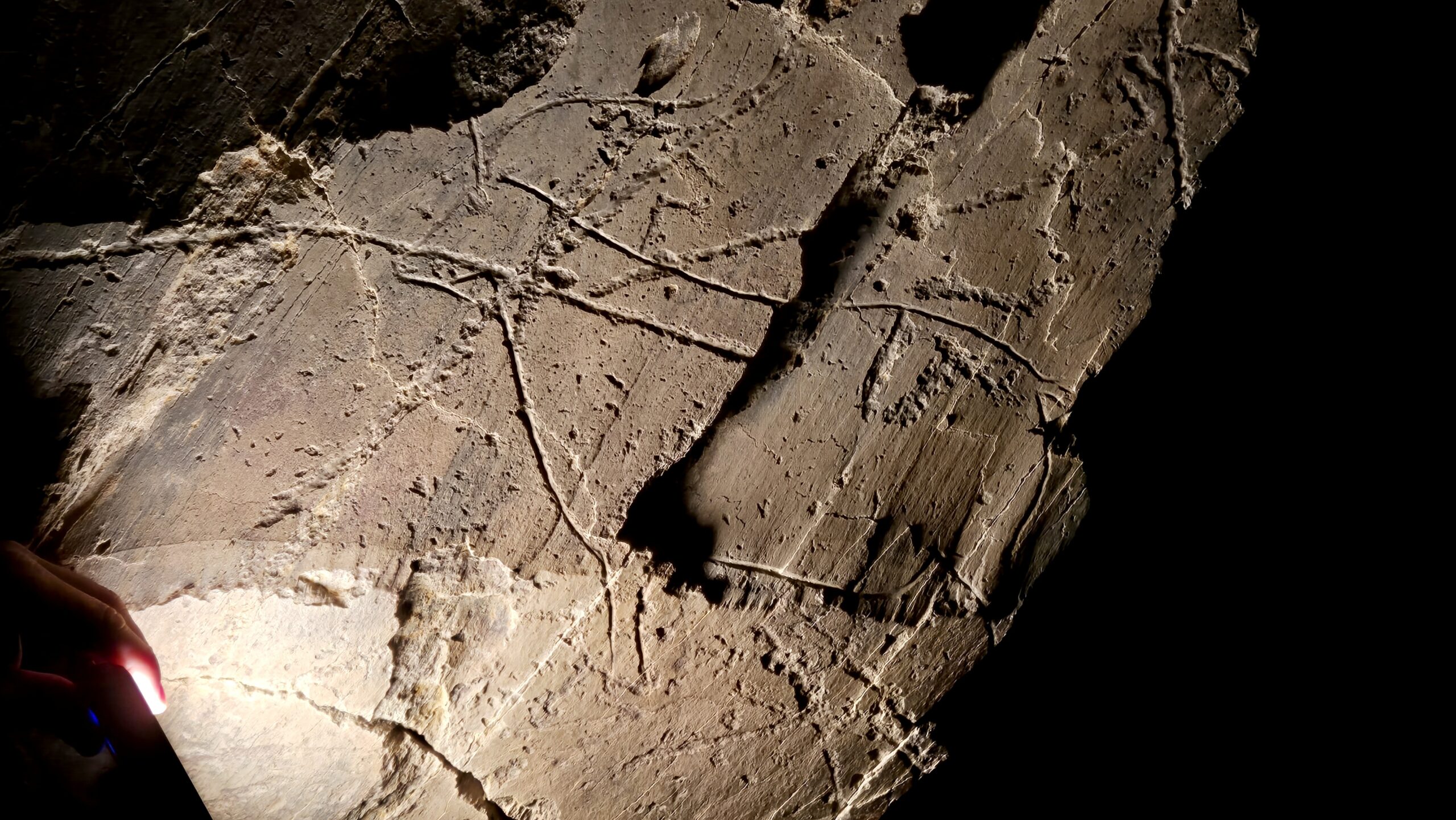

We did two hikes into the 30-kilometer long valley, where to date over 1000 inscribed rock faces have been found and painstakingly transcribed. One hike was at night, when flashlights could highlight the delicate lines of the engravings – before the constellations rounded out the tour. The other hike was in morning light when we needed to peer intensely at the barely visible artworks. Both were amazing.

The confluence of two rivers that have attracted settlers for at least 30,000 years. That’s the Douro on the left and the Côa on the right, with the hills terraced for wine growing.

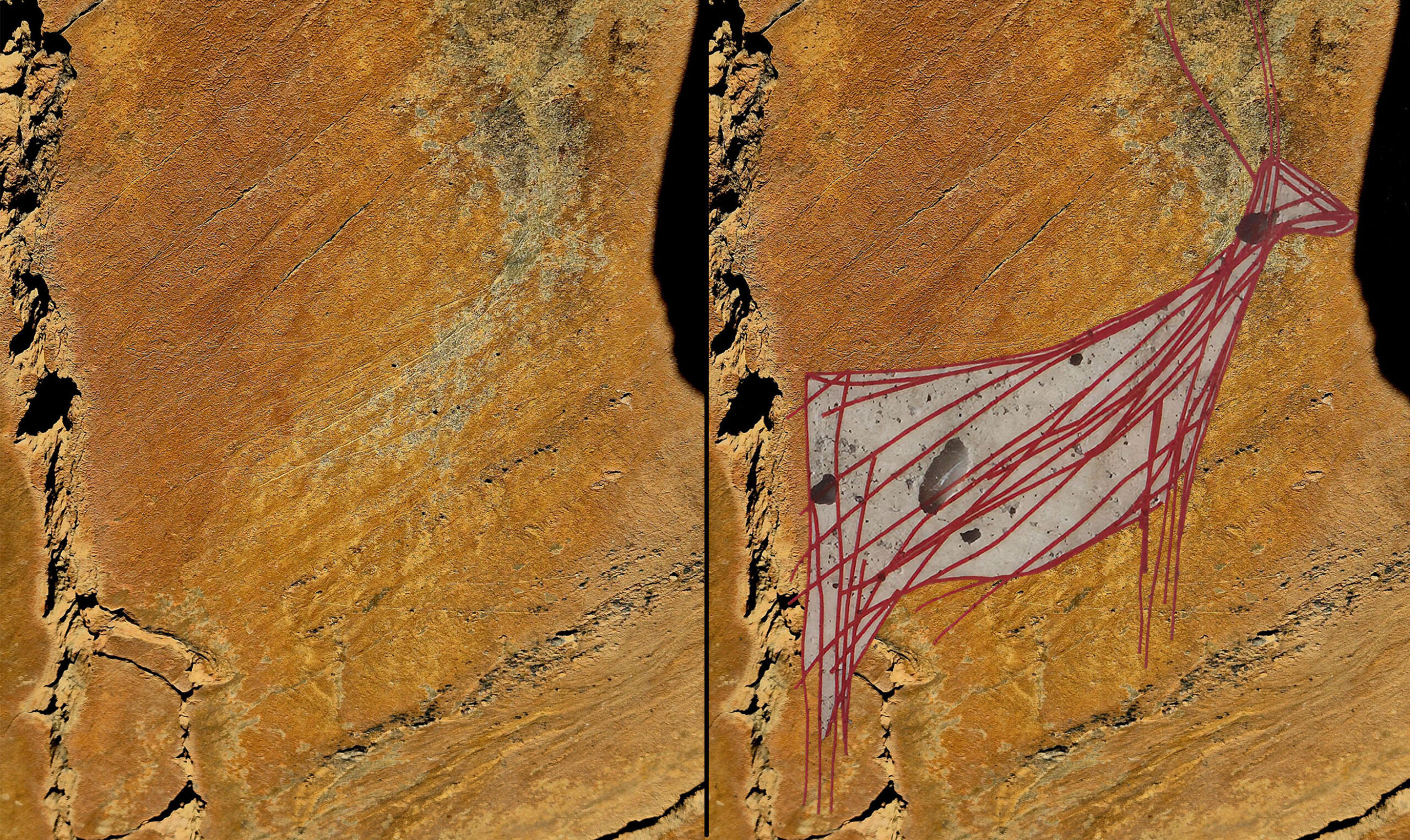

As you can see from this one example on the left, the fine lines of these ancient engravings are hard to detect from photos taken during the daytime tour. On the right is the same rock, but with an overlay of the transcribed deer. Its body, not just outlined but filled with fine scratched lines, is the symbol of the archeological site.

Our first sighting, and an unusual one for the area, was this stag. If you look carefully, you can see the etched head staring out at you beneath the antlers.

A typical set of engravings on a rock face about a meter (3 feet) high. At least a dozen animals mount the surface. You can probably detect the bull looking to the left just below the middle of the rock. And then there’s a horse overlapping it, but looking to the right. A goat stands around its hooves. And so many others join the herd above the bull. Some rocks appear to be “hot”: for whatever reason, they proved to be worthy of these engravings- while adjacent rock faces received nothing. Several people today have devoted themselves to creating detailed facsimiles of the original drawings, however complex the originals were.

When originally carved, and perhaps colored, this bull stared across the river at an identical one looking over toward it. Start with the tail and the bold line of the back to the left, then follow that to the right to see the horned head looking back at you – and its mate across the river.

Again start with the vivid back to find the upraised tale of this goat to the left, the horned head to the right, and then move down to the foreleg, bent as if the goat is moving.

Another goat. The boldest vertical line on the left is the chest of a goat rising to its delicately horned head. You can then follow its back and legs from there. Notice the representation of its beard beneath its jaw.

The horse looking to the left is pretty clear, but see if you can find the other horse overlapping it, with its head bent to the right to graze. And then there’s a goat emerging from the chest of the first horse. And two more moving up and to the right from that same horse’s back.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Portugal as of 2025, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page. To see a slideshow of photos between 2017 and 2024, CLICK HERE)