Albania’s history can read like a tale out of Tolkien’s Ring trilogy. It starts before the 4th century BC with the sophisticated tribes loosely known as the Illyrians. The land since then has been at the border of the contention between religions and empires: east and west, Rome vs Constantinople, Christianity vs Islamic Ottoman, Communism vs capitalism. (For our observations on Albania today and its readiness for visitors, click to see that post. Or click here to read about the imprint of all these cross-currents in the still visible antiquities within the country.)

Not surprisingly, Albania’s culture and language have been strongly influenced by all its invaders. Surprisingly, since the First Millenium the people here have retained a strong sense of their own cultural heritage as Albania and their own language, distinct from nearby Serbo-Croatian or Greek.

Perhaps this stalwart self-assertion relates to the heroes celebrated here. We often find we understand a lot about a society by those it celebrates as heroes. In Slovenia, for example, the country mainly celebrates its poets and writers. In Albania, the country’s heroes are largely those who futilely resisted domination by outside forces.

The most celebrated of these is the 15th century leader, Skenderbej. Gjergj Kastrioti was a prince in Albania when the country was subdued by the Ottomans. As was their custom, he was taken as a kind of booty and raised in Turkey, where as Skender (from Alexander or Iskander) he became a renowned warrior and chieftain (or bej). He returned to Albania and rallied his native people against the Ottomans. For decades, he cleverly repulsed their much stronger forces. When he died, however, the resistance dissolved and the Ottomans ruled once again. He is celebrated in so many ways, including a massive statue in his eponymous central Tirana square, as well as with a massive room of the National History Museum detailing his military prowess.

By contrast, we just happened to learn about Queen Teuta of Illyria who actually defeated the Greeks in the 3rd century BC after they had overrun the land in the century before. Albanian Illyria however was soon taken from her by the Romans. The only thing we saw in her name was a grocery store on the Albanian Riviera.

After the Romans, Albania found itself on the border of the religious division of Christianity, with the Byzantine empire of the east taking control in the 6th century AD against the Roman religion. Though interrupted by the invasion of “barbarian” tribes such as Huns and Serbs, that contention continued into the late middle ages and renaissance.

By then the Venetians dominated the Adriatic coasts, alternately sweeping away the growing power of the Ottoman Empire and, in turn, being swept away. By the 1600s, the Ottomans dominated the region until 1914.

Across the country – notably in Butrint, Shkoder, Berat and Durres – you can see the physical evidence and the archeological record of these contending forces – the Illyrian base, the Greek influence, the Roman cities and fortifications, the Byzantine architecture, the Venetian improvements and finally the Ottoman enhancements.

By the time the Ottomans took over, the Albanian language had already formed, most likely from Illyrian, mixing with Latin, Greek, Serbian, German and other Baltic tongues – those empires that swept in and out of the area. As a result of this amalgam – and with 36 letters in their alphabet – Albanians, we were told, can form most of the sounds of other world languages, so they are fine linguists. In our experience, many can speak English, Italian, Greek, French, Serbian or German.

The long rule by the Ottomans did ensure that the majority of people in Albania were Muslim, though eastern and western Christianity remained strong. Every neighborhood had its mosque, many of which still stand. Some towns like Gjirokaster and Berat are filled with 19th century homes built by wealthy Ottomans, and still demonstrate their way of life.

By the start of WW1, the Austro-Hungarian empire had already subsumed the region west up to Serbia, so Albania was pretty much the border between that empire and the Ottomans. Even 25 years before the Balkans set off the Great War, and with all its history in mind, the Prussian leader Bismarck understood where Albania and the Balkans stood: “One day the great European War will come out of some damned foolish thing in the Balkans.” And it did.

The 20s and 30s were a bit different for an independent Albania, principally due to the modernizer King Zog the first, a self-declared ruler after taking power politically. He was autocratic and suppressed civil liberties, but he reconciled the religions of the country, modernized Albania culturally and physically, and instituted a civil rather than religious code of law.

By World War 2, Mussolini’s Italian forces took over again. Albanians naturally lionize the fighters who resisted the invasion and occupation of the country, though there were no successful Skenderbejs this time. Those resistance forces were primarily Communist, so the end of the war brought the Communists to power within the country. They proved to be a strong, disciplined organization; and, to the people, they had been the heroic resisters.

Sadly, unlike the relatively enlightened rule of neighboring Tito in Yugoslavia, the Communist party soon produced the mad 40-year dictatorship of Enver Hoxha. Hoxha gruesomely followed the same template as other Stalinist or Maoist leaders: iron-fisted control, paranoia, murder or imprisonment of imagined enemies and intellectuals, and horrid punitive measures against resisters. He oppressed the family members of those who opposed him in any way. All of these led Albania into a dark hole that it’s still climbing out of. As exhibits at the National Museum demonstrates, those futile resisters to Hoxha are now exalted as heroes – in sharp counterpoint to the socialist realist mosaic adorning the building.

Over time, Hoxha increasingly cut his country off from the world, first the west and then other Communist countries as they eased their rigid adherence to Communism. By the 1980s, he had effectively walled Albania off from all others, impoverishing the country by forcing it to be self-sufficient despite limited resources. The closest equivalent to what happened is North Korea, though even it has one ally in China.

The average person suffered with meager food and supply rations, particularly toward the end of his regime. There were no cars, no freedom of movement within the country. The leadership could boast that all the people, including women, had jobs but these were make-work things. Oddly, healthcare was surprisingly good and education strong through high school. Yet, media consisted only of propaganda and music considered safe – classical and traditional Albanian folk tunes. Religious practice was virtually banned, with hundreds of those mosques and churches destroyed or converted to warehouses or sports halls, for example.

Literally, concrete evidence of Hoxha’s madness is still visible all around the country – in cities, beaches, mountainsides. To protect a population of 3 million, he ordered the construction of 75,000 to 750,000 concrete bunkers (the numbers seem to depend on your source). These were intended as refuge from the nuclear threat during the Cold War as well as defensive emplacements against imagined attacks from Albania’s enemies, most of which barely knew Albania existed.

These virtually indestructible concrete bunkers range in capacity from the individual to the small group to a virtual office building underground, like the one in Tirana and the one we visited in Gjirokaster, Hoxha’s home town. Gjirokaster’s bunker could accommodate 500 of the top echelon party and city leaders, but was completely unknown to the townspeople otherwise.

In 1991, when the regime fell five years after Hoxha died, people could not quite comprehend what was happening. After all, they assumed that the rest of the world was like Albania. Suddenly, imports like bananas were available, though our guide noted how afraid his mother was of that fruit when she first encountered it. Cars arrived, most notably Mercedes, which Albanians still have a penchant for. Teenagers found western music, especially the hardest of metal, a way to express their freedom – and rage. They donned jeans and listened loudly to Metallica; the boys grew long hair and were indistinguishable in photos from the girls.

Some Albanians found ways to get wealthy, creating, for example, Ponzi schemes that naïve Albanians thought was the working of capitalism. Other institutions crumbled, along with the quality of education and healthcare. Albania became a democracy, but a struggling one. Corruption became a way of life.

The country slowly began to emerge from its dark ages, with support initially from the US, notably under George W. Bush and then under Obama (and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who is honored by a statue in the center of Sarande). The EU has invested heavily as well. In our second post on Albania, we describe what we observed during our visit 25 years later after the fall of Communism.

In the middle of Tirana, Albania’s capital, you can follow the sweep of this history at the National Museum. You can check out the ruins of Byzantine rule with the remains of the Justinian fortress, as well as the remnant of the Ottoman walled fortress that supplanted it. Ottoman mosques date from hundreds of years ago. And, at neighboring Durres, you walk bits of Roman, Venetian and Ottoman rule.

And you can see the now closed home of Enver Hoxha in the hip Blloko district, once restricted to the bigwigs of the Communist party. You can try and reach the freedom bell, a large bell forged from military hardware, which can only be rung by some with a leaping effort. Most leaps are futile.

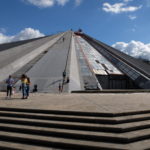

Next to it rises the Pyramid, built in the late 80s as a memorial to Hoxha and a glorifying museum. In the 90s, it was turned into a public building and then a nightclub. Now it’s almost derelict, whileTirana debates whether to destroy it or turn it into something else.

Fittingly, it’s a concrete and glass bunker of a building, a tourist attraction whose main use currently is to entice brave souls to mount its steeply pitched walls, briefly celebrate at the top and then descend precariously back to the ground.

(Also, for more pictures from Albania, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)