In brief: We explore the desert cities in the east: Riyadh, the expanding capital; Buraydah, a crossroads for trade; and Hail for ancient art.

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia – a land with a rich past mostly unknown to westerners. You can trace thousands of years of history, carved in stone or written in manuscripts, at this crossroads between cultures. In recent history, many tribes warred to control its resources until, beginning in 1902, Abdulaziz of the Saud tribe eventually unified the country under his rule from Riyadh.

Earlier in 2025, we had visited Al Hasa, the renowned World Heritage oasis between Riyadh and other Gulf States like Qatar. To read about that visit, see our Al Hasa posts.

Riyadh, the Capital

Riyadh is huge, a sprawling city of 8 million, which rapidly continues to be transformed. Few old things remain to be seen, like the city walls that were pulled down a while ago. Other historic structures have been restored or reconstructed, looking as good as new in many cases, largely to educate the young about the past – or, now, to entice tourists.

The legendary 1865 Masmak Fortress where, with courage and stealth, Abdulaziz overthrew the ruling Al Rashid tribe in 1902. This began the Third (and current) Saudi Empire, during which he united the provinces and tribes into the one country of Saudi Arabia. Located at the heart of early 20th century Riyadh, the fort has been fully restored to look newly made. The architecture demonstrates the Najd style of the east: clay brick walls reinforced with straw, the small holes for ventilation and viewpoints, plus white detailing around inner windows and around rooftops.

Some of the delicately etched wooden doors of the 19th century Masmak Fortress plus the typical Najd use of triangular features.

The traditional Najd architecture of the royal residence of King Abdulaziz after he united the country. We could view the exterior, but the inside of the palace was closed. Note the triangle designs, the white trim including the runners at the roof-line, and the bridges that allowed passage between the king’s quarters and the residence for wives and children without going outside.

The governmental center in old Riyadh, though nothing looks very old here now. This is Al Safat (“wide smooth stone”), where camels and weapons were traded once. More notably, it is also called Justice Square because public punishments including beheadings used to take place here, but not anymore. Its more macabre name was “chop-chop” square.

Just like the recovery and rehabilitation of the past, this is a place for big plans. Nothing is small. Not the restaurants, nor coffee shops, nor new complexes like the 135-kilometer long sports facility being built to cross the city from east to west, or a massive new entertainment center where the old airport operated, or a whole new central city near the revived old one of Diriyah, where a forest of cranes operate.

The palace of Imam Abdullah bin Saud in the older 18th century Diriyah district during the First Saudi Empire. The remains of this original city in northern Riyadh are a World Heritage Site due to their cultural importance. You can see here the results of the ongoing restoration work, blending the rough, old stones with reconstruction using the same methods as the old (brick and clay mixed with straw). The palace clearly shows those tiny triangular windows frequent in Najd architecture.

A part of 18th century Diriyah yet to be restored, demonstrating the condition of much of it before the renovation work. In the mid-ground are the palms of the oasis that fostered the old city. And in the background, the forest of cranes marks just one of the huge projects ongoing in Riyadh. This one, as big as a whole city in itself, comprises a massive additional living and entertainment complex – one of the plans in the Vision 2030 program.

All of this activity in Riyadh, and in the rest of the country, is part of leadership’s Vision 2030 program, looking toward a future economy not so reliant on oil. Like other Arab states, the leaders aim to boost tourism, entertainment, sports, business investments, and so on – even alternative energy like plentiful solar.

Catching the rays…On the road out of Riyadh, we were astonished by what seemed to be a dark blue sea running alongside the road for 4 kilometers (2.5 miles): it was, actually, a 4 x 4 kilometer solar farm. We have also seen expanses of wind turbines at work.

Many new skyscrapers like this one rise out of the flat landscape of Riyadh, and there are some groups like the new Financial District, but Riyadh does not yet have the large skyscraper clusters of some Gulf States. The older villas in the adjacent neighborhood (seen at the base of the pyramid) are slowly being renovated or replaced.

An inviting park in old Riyadh. New parks around the country could be considered entertainment complexes, but this lovely one featured flowering plants, a modern art installation, and preparations for a light show during this week’s evening celebrations of the city. The old city is now one of many “centers,” scattered across long stretches of the city where traffic is regularly stalled in every direction despite the network of wide 6+ lane roads and highways. These form a kind of grid; within the sections of intersecting main roads, you find warrens of single-family homes or small apartments. The gleaming metro system of 176 kilometers and 85 stations is just starting to help move people faster. More lines are in the works.

A section of park near Diriyah featured hedgerows and date palms. This pays tribute to the vital role of oases and their abundant palms in desert life, as well as in the agricultural economy. The additional water required for farming and drinking is all pumped from desalination stations on the coasts. So, Saudi Arabia now supplies a wide range of fresh vegetables and fruits (including berries) to its markets.

The Edge of the World…outside Riyadh

It’s the Edge of the World, as we know it…and we were fine. On an escarpment of multi-colored sandstone that rises abruptly to 600 meters (about 2000 feet) over the outskirts of Riyadh, we hiked and danced. And peered at the vast sweep of land sprawled far below us. That’s why, here in Saudi Arabia, they call it the Edge of the World.

It was mind-blowing to follow the trails around the crumbling edge. And mind-blowing also to find fossilized shellfish, coral, fish, and wood there! For we were actually walking along an ocean bed from millions of years ago.

A fossilized fish discovered amid the rocky shale and sandstone of the escarpment. We saw many fossils of shellfish and coral as well.

With our savvy guide Hashem Alshareef at a canyon carved by the occasional water flows atop the escarpment.

Picture perfect at 600 meters.

On the Edge. We learned later that the escarpment continued to the west of KSA, turning into the mountainous region that parallels the Red Sea.

Buraydah: A Stopover with Legs and Arms

It seemed like a pleasant mid-sized town, a stopover after the big city of Riyadh, but with few sites of interest to a visitor. However, we were delighted to find one of the largest camel, sheep, and goat markets in the country as well as a sprawling date market called Date City – both a result of the large oasis farms that made Buraydah an important economic force in the country. Oil is king now; but water from oases or springs owned the past. And we were charmed by a family history museum, whose collectibles showed how trading across the Arabian Peninsula enlarged the city’s economic importance. The town proved a lot bigger than it seemed.

We were invited into one tented stall at Date City to sample a few dates, exchange introductions with the farmers, and then wriggle out of purchasing huge boxes of the fruit. Date City consists of a few large buildings and a parking lot for many sellers, but we happened to be there when things were oddly quiet. Bad dates?

Buraydah has a much more formal market for domestic animals than the wilder one we saw at Nizwa, Oman. Here a buyer is checking out one camel, whose leg has been tied up briefly to keep him from moving.

Nancy checks out a herd of goats that had been running wildly away from their Yemeni goatherds, who stopped to talk with us.

“No, sorry, we’re not taking you home with us…”

The Al-Oqilat Museum crams more than ten thousand documents, photos, tools, maps, and stuffed camels within its old family dwelling.

The displays illuminated centuries of trading by the al-Oqilat tribe across the Arabian Peninsula and into India – as well as much of Saudi history. This is the reception room where visitors now gather for the traditional welcome of coffee and dates, often with the heir to the museum who is gesturing at the left of the picture. In the past, purchases of camels, goats, textiles, weapons, and more were finalized here under the thicket of sticks that form the ceiling.

A lounging room for visitors with typical Najd decorative features and a display of coffee pots and tray service. The adjacent room focused on the Arabian horses used by the tribe.

One of many gorgeous doors within the Al-Oqilat Museum.

A typical inner courtyard for a home, at the Al-Oqilat Museum. The white bell-like trim of Najd architecture makes such a contrast with the beige clay walls. Some other features are not typical, like the constant trickling of water at the well to the lower right (with a traditional water bucket made of camelskin), the swooping of birds from perch to perch on the rooftop, and the stuffed camel. The camel was one of a half dozen or so on display in various rooms, presumably old companions of the traders.

Hail and Jubbah: High and Low

Hail seemed a typical Saudi town, with the usual residential streets in a grid with major commercial arteries crossing at regular intervals. Add a few green spaces and an historic fort hung atop a lone mountain and you have a pleasant Saudi town.

Hail

The A’arif Fort dates from around 1840 under Rashidi rule. Its traditional mud-brick construction was common at that period, but most examples are gone now.

The view over Hail from the parapets of the fort.

Late in the day, several groups of visitors arrived at the fort, including these young Saudi women who stopped to talk with us and a family group that also introduced itself.

Jubbah

The World Heritage site at Umm Sinman in Jubbah, about an hour from Hail in northeastern Saudi Arabia, is an open-air museum of drawings and messages dating back 8000 years. Nomads, traders, and more permanent dwellers scratched their thoughts on sandstone cliffs, an early form of social media that has endured till today. The oldest are stick figures and domestic animals. The most abundant come from the Thamudic period in the 2nd and 3rd millennium BC: warriors astride camels and horses, realistic animals like ostriches and ibex, thousands of them, as well as 5400 texts still read avidly by archeologists. Early Arabs added camel riders holding reins and images of everyday life. And Muslims then recorded extensive thoughts and prayers to seek for peace on their journeys. Jubbah’s open-air classroom delivered a fascinating history lesson.

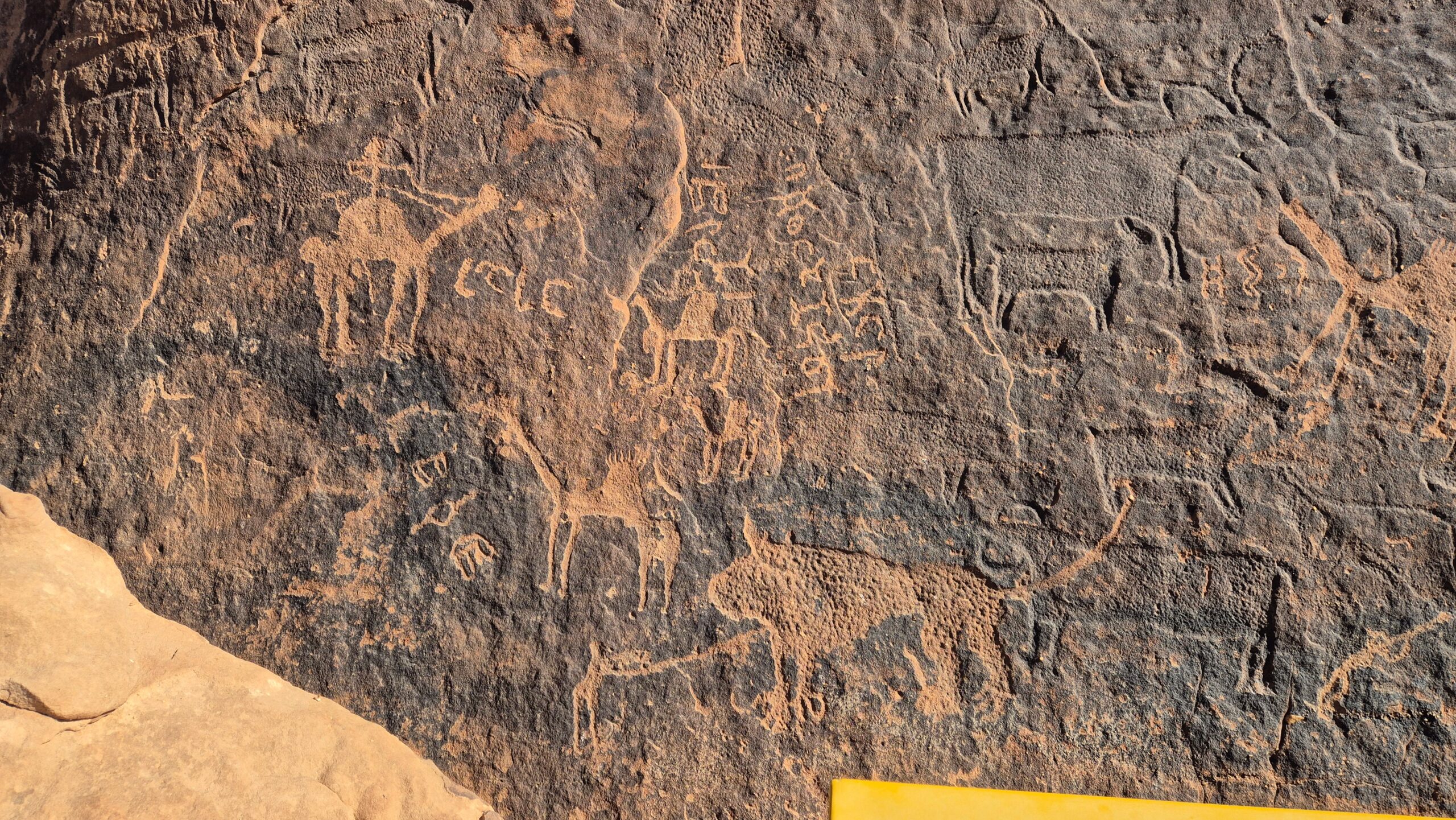

Not just a pretty face. We nearly missed discovering what’s here: hundreds of figures and inscriptions from the distant past cover the darker stone. We just needed to look a bit closer…

On the dark patches of that landscape, per the image below, you can see the density of activity often found on walls here. Neolithic stick figures appear amid camel trains, ibexes, and goats. On the panel above, Thamudic text messages abound from thousands of years ago.

On the right side of the following panel, we found an unusual representation in this region of a chariot drawn by two horses, guided by the little figure astride the horse to the right. Nearly all drawings show side views; this virtually adopts the perspective of someone between the two horses. It dates from the Thamudic period about 1500 BC. Other images have been worn away, but notice the long shadowy man etched into the stone during the earlier Neolithic period. To his left, a very detailed ibex: its curved horns carefully show off their ridges. And the later figures above it, which seem to show a fight between a mounted warrior and one on foot. Plus, on the rock to the left in the background, an Islamic inscription from more recent times.

A full slate: a hunting scene on the right with a fully armed man hunting for food, beyond which sits a curious spidery thing. A large bull hovers contentedly in the center amid other domestic animals. Carved more deeply at the back end of the bull is a Neolithic human figure with sinuous legs. To its right, ancient Arabic text runs vertically. Scattered above the bull are a herd of wild oryxes, with their long straight horns. IMs from thousands of years ago.

The next photo shows a portion of one of the most interesting and densely covered walls at Jubbah, with a wide array of periods and styles. In the center, a number of camels wander about, but the one toward the upper left is being vigorously driven by a rider holding the reins. That’s a lion with sharp claws at the bottom near the yellow marker, with perhaps a brave man keeping it at bay. To their right, carved deep into the surface from top to bottom are neolithic figures of cattle including what seems to be a calf inside a cow at the top, and various horned beasts. More wander across the top. In other parts of this wall, one could see similarly engraved long, lean neolithic humans. And ostriches!

In several places at Jubbah, figures likely to be priests or royals conducting some ceremony appear as larger images.

For more of rock art in the country, see our post on the south of Saudi Arabia.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Saudi Arabia, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)